Advertisement

- Updated on May 15, 2025

- IST 4:52 am

“The taboo that stole India’s first women’s Olympic medal.”

Sports have a magical way of uniting us, don’t they? Whether it’s the thrill of a cricket match going down to the wire or the breathless anticipation of an Olympic race, these moments etch themselves into our hearts. For India, one such moment came in 1984, when PT Usha, a sprinter from Kerala, stood on the brink of history. She finished fourth in the 400m hurdles at the Los Angeles Olympics, missing the bronze medal by a mere 0.01 seconds. It was a performance that showcased her extraordinary talent and grit, but it also left us with a lingering question: what if?

What if the support systems had been different? What if the societal taboos surrounding women’s health—particularly menstrual health—hadn’t cast such a long shadow? This isn’t just the story of a race; it’s about the unseen struggles female athletes like PT Usha faced in an era when period stigma was a silent barrier. For an Indian audience aged 15 to 45, this is a tale that blends pride with a call for change—a chance to honor a legend while reflecting on the challenges she overcame. So, grab a cup of chai, settle in, and let’s dive into PT Usha’s journey and the taboo that might have stolen India’s first women’s Olympic medal.

PT Usha’s Journey: The Payyoli Express Takes Flight

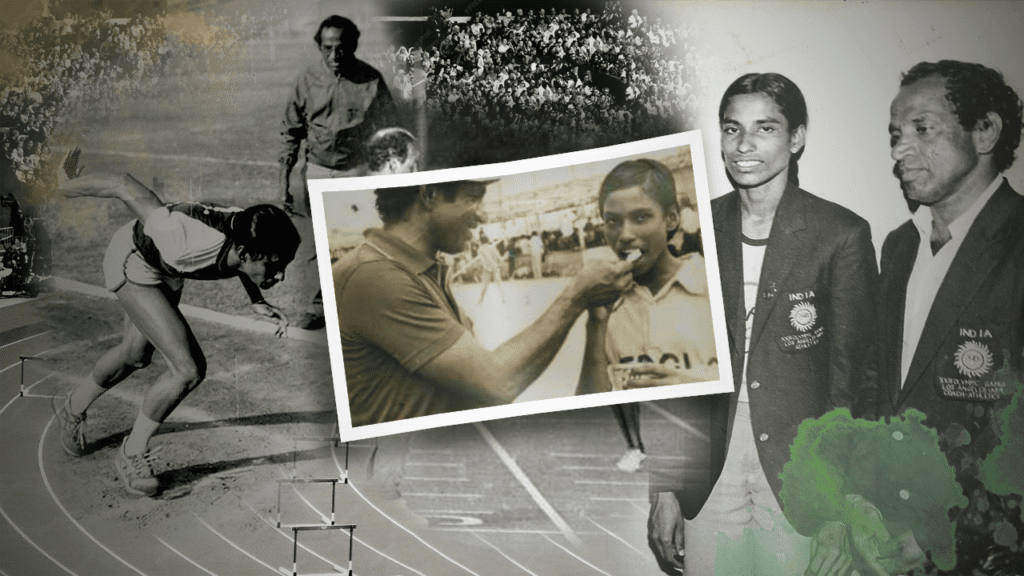

Imagine a young girl from a small village in Kerala, running barefoot on dusty tracks, her speed turning heads in a place where sports weren’t yet a common dream for women. That’s where PT Usha’s story begins. Born in 1964 in Payyoli, she was discovered by coach OM Nambiar, who saw a spark in her that could light up the world. Under his guidance, Usha transformed from a local talent into a national treasure, earning the nickname “Payyoli Express” for her lightning-fast strides.

By 1980, at just 16, she was competing at the Moscow Olympics—a feat that felt like a dream for a country still building its sports legacy. Though she didn’t medal there, it was a stepping stone. Through the early ‘80s, Usha dominated Asian athletics, bagging silver medals in the 100m and 200m at the 1982 Asian Games and a gold in the 400m at the 1983 Asian Championships. Her versatility was jaw-dropping—sprints, hurdles, relays, you name it, she conquered it.

As the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics loomed, Usha zeroed in on the 400m hurdles, a new event for women that demanded both speed and precision. She trained relentlessly, and her pre-Olympic performances—like beating American champion Judy Brown—hinted at something big. For a nation hungry for Olympic glory, PT Usha wasn’t just an athlete; she was hope in motion.

The 1984 Olympics: A Heartbeat Away from History

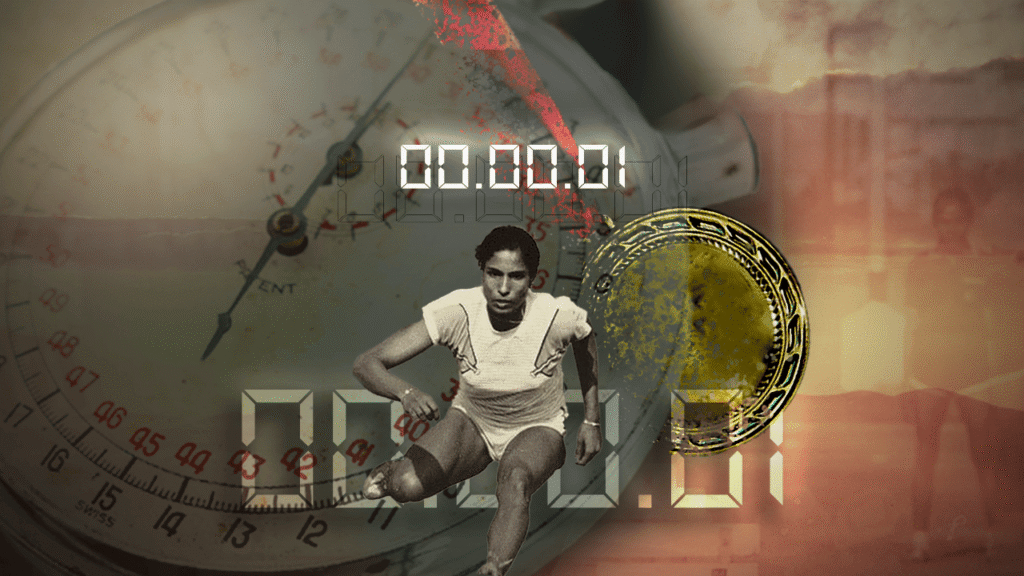

Picture this: it’s August 8, 1984, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. PT Usha steps onto the track, the first Indian woman to reach an Olympic final in athletics. She’d already breezed through the heats with a time of 56.81 seconds and smashed a Commonwealth record in the semi-finals with 55.54 seconds. The final was her shot at immortality, and India was watching with bated breath.

The lineup was fierce—Morocco’s Nawal El Moutawakel, the USA’s Judi Brown, and Romania’s Cristieana Cojocaru among them. As the runners took their marks, the air crackled with tension. Then, a hiccup: Australia’s Debbie Flintoff triggered a false start, forcing a restart. For Usha, known for her explosive starts, this could’ve thrown off her rhythm. When the gun finally fired again, she was a fraction slower off the blocks but fought her way back, hurdle after hurdle.

The final stretch was a blur. Usha and Cojocaru were neck and neck, lunging for the line. The crowd held its breath as officials reviewed the photo finish. The verdict? Cojocaru took bronze with 55.41 seconds; Usha finished fourth at 55.42—just 1/100th of a second behind. Devastation and pride collided. She’d made history, yet missed the podium by the tiniest margin imaginable.

The Silent Struggles: Challenges of Women in Sports India

To grasp the weight of PT Usha’s feat, let’s step back into the India of the 1980s. Sports were a man’s world, and women who dared to compete faced skepticism, limited resources, and societal norms that boxed them in. For female athletes, the hurdles weren’t just on the track—they were in the lack of funding, sparse facilities, and the cultural expectation to prioritize family over ambition.

Then there was the unspoken challenge: menstrual health. In a country where periods were—and sometimes still are—whispered about in shame, female athletes had to manage their cycles in silence. No fancy sanitary pads, no open chats with coaches about cramps or fatigue—just grit and guesswork. Imagine training for the Olympics without knowing how your body might betray you on race day, all because talking about it was taboo. For PT Usha and her peers, this was reality.

Coaches, mostly male, often didn’t know how to address these issues—or didn’t want to. Training regimens ignored the ups and downs of a woman’s cycle. Nutrition advice? Barely tailored. In a way, these athletes were running against more than their opponents—they were racing against a system that didn’t see them fully.

Period Stigma in Sports: The Hidden Hurdle

Period stigma isn’t just an Indian problem—it’s a global one, but it hits harder in places where silence reigns. For athletes, menstruation can be a game-changer. Cramps can sap your strength, fatigue can dull your focus, and hormonal shifts can mess with your headspace. Studies today tell us the menstrual cycle affects performance—some women peak in the follicular phase, others falter in the luteal. But in 1984? That science was a whisper, not a shout.

Back then, female athletes like PT Usha had to figure it out alone. No period-tracking apps, no sports doctors specializing in women’s health—just raw determination. If you were on your period during a big race, you pushed through the pain or risked being sidelined, no questions asked. Coaches might’ve blushed at the mention, and teammates might’ve stayed mum. The result? A hidden hurdle that could’ve tipped the scales in a race decided by 0.01 seconds.

Fast forward to today, and athletes like PV Sindhu or Britain’s Jessica Ennis-Hill talk openly about periods affecting their game. It’s a shift PT Usha’s generation paved the way for, even if they couldn’t enjoy it themselves.

PT Usha’s Experience: Could Period Stigma Have Played a Role?

Here’s where we tread carefully. There’s no interview or record where PT Usha says, “My period cost me that medal.” She’s spoken about the false start throwing her off, the emotional gut-punch of fourth place, and the encouragement from Indira Gandhi that followed. But menstrual health? That stays off the page, and we respect her silence.

Still, let’s think about it. The 1984 final was a high-stakes moment after months of grueling prep. Given the era’s lack of menstrual support, it’s not wild to wonder if Usha was battling more than just her rivals. Maybe she was cramping mid-race, or maybe fatigue hit harder that day. We don’t know, and we won’t claim it as fact. What we can say is this: for women in sports in India back then, period stigma was a real foe—one that could’ve tilted a race this close.

Her story isn’t diminished by this possibility—it’s elevated. She ran that final with everything she had, against odds we can only imagine, and came within a heartbeat of glory.

Legacy and Progress: The Torch Passes On

That near-miss didn’t stop PT Usha. She returned to dominate Asian athletics, racking up medals and inspiring a nation. Her Usha School of Athletics in Kerala has since churned out talents who carry her torch forward. She’s proof that setbacks don’t define you—your fight does.

Since 1984, things have shifted. Menstrual health in sports is no longer a dirty secret. India’s government and sports bodies are pushing for better resources—think sanitary pads at training camps and coaches trained to talk periods without flinching. Globally, research is unpacking how cycles affect performance, giving today’s athletes an edge Usha never had.

But we’re not there yet. Rural athletes still lack basics, and some coaches dodge the topic. PT Usha’s 1984 miss reminds us why this matters—because no one should lose their shot at history to a taboo we can break.

Conclusion: Let’s Keep the Conversation Going

PT Usha’s 1984 Olympic story is a rollercoaster of pride and what-ifs. She gave India a taste of greatness, even if the medal slipped away. Whether period stigma tipped that race or not, her journey shines a spotlight on a fight bigger than one athlete—it’s about every woman who’s run, jumped, or swung against the odds.

So, as we cheer our stars at the next Olympics, let’s push for a world where no athlete’s potential is stifled by silence. Share your thoughts below—did PT Usha inspire you? Have you seen period stigma in action? Let’s talk, learn, and lift up the women in sports India cherishes. Together, we can make sure the next PT Usha crosses the line with nothing holding her back

You May Like This

Advertisement

You May Like This

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement